The music industry is hype again! A story about how the cause of the music business meltdown is also feeding its current exponential growth, and how this new prosperity could/should cascade to all players in the industry.

Damn, it’s growing again!

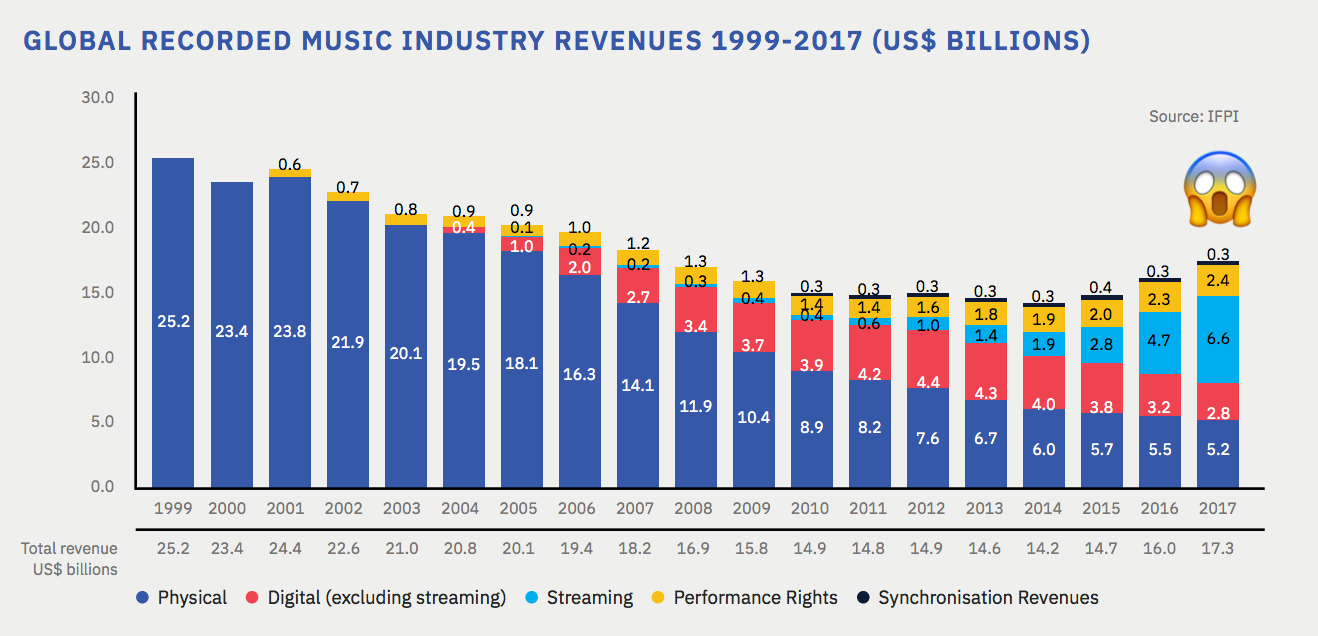

After 20 years of continuous decay, the recorded music industry has been regaining some colours for the last couple of years. Thanks to streaming which is dragging the whole industry back on its feet, the recorded music industry experienced 8.1% global revenue growth in 2017. Business Insider even predicts that the market could… double by 2025 to reach a record-breaking $30 billion ($17.3 billion today) 🚀

But guess what? The foundations for this remarkable growth lie in the very reason why the music industry sunk in the first place: pure technological innovation.

The .mp3 or the irruption of a technological marvel

In 1995, following a contest dedicated to defining an international norm for audio compression, the mp3 is invented. But this technological marvel – which required the conjoint work of giant manufacturers and psychoacoustic specialists from all around the world – is about to end up a complete failure. As Sophian Fanen explains in his book Boulevard du Stream (2017), its inventor Karlheinz Brandenburg has to face the rejection of his mp3 encoder from all big players in the music industry:

“The executives from BMG listened to him politely while he was talking about kilobytes by second and bandwidth, then reminded him that their job consisted in selling CDs and escorted him out of the room”

Ouch! But too much money has been dedicated to research for Brandenburg to give everything up. So he does the only thing he can: let everyone access the mp3 encoder for free and rather sell the license of the decoder. He does not know it yet, but his decision is the first key to a dream come true for music addicts: music available and exchangeable online.

From CD to downloads to streaming, technology replacements in clusters

In 1996, the first mp3 is published. But low speed internet hinders its development for a time. Even in 1999 when Napster launches the first peer-to-peer exchange platform, the music industry is rather panicking about burned CDs at Midem.

Everything’s going too fast for the big fishes, and nobody knows where to look. Burners, digital cassettes — yes, it almost was a thing — , MiniDiscs — if you’ve got one at home, you can start a museum — , and finally no medium at all. Big manufacturers are the first ones to understand the announced separation of music — the content — from the physical medium. Philips sells Polygram in 1998, even before Napster was created. On the content side, the “majors” overestimate their customers’ ears and think the mp3 quality is too low to seduce them. They should have led a few customer interviews first… Because they are on the verge of getting slapped in the face.

You’ve never seen this? That’s completely normal.

No business model to online music! (?)

In 2002, the music industry succeeds in closing down Napster. In 2002, the music industry starts dropping down. How could an industry which revolved everything to the excess around a physical product — the CD — adapt when its essence — music — is exchangeable and transportable for free? There is no business model to online music! The whole revenue of the recorded music industry still comes from selling CDs even though sales are plummeting, so the majors protect the way it worked until then. I wouldn’t be surprised if a few music execs would possess a voodoo doll with the effigy of Karlheinz Brandenburg a few years later…

France affected after the rest of the world, like in the 1930s

In 2001, thanks to Star Academy and Popstars — but also slower Internet connection — , the French music market explodes (+10.8%). Is France an alien? Or is it just a brief respite? It is a common thing. Usually for a few peculiar reasons, crisis touches France with a delay. Like in the 1930s, the Wall Street Crash of 1929 started affecting France in 1931. Only to hit it hard all of a sudden.

Downloads, a 10-year cycle

Paying to download tracks online. In the frenzy of this new online music world, more and more startups — such as francemp3.com — secure funding on this idea in the context of a financial bubble. Not only do they need to face the fact that people can easily download tracks for free on other platforms, but majors refuse categorically to bring them their catalogs. Or worse, they make them pay extraordinary sums of money only to watch them die a few months after. Why? The veterans protect their bread and butter: the CD. Fierce ‘free’ competition on mp3 is facing a wall.

Not only did Apple convinced the majors to join the band, its platform was incredibly better designed than all the others. Yes, this was sexy design in 2003.

The iTunes Store is launched in 2003 and progressively convinces “majors” to join in. It is a turning point. Thanks to a nice design — the trademark of Apple — and finally a large catalog, they eat the bigger share of the cake and put an end to the entrepreneurial frenzy. As sales of CDs are falling down, time is for growing the new downloads market. First years are promising, but piracy is still an issue. In France, regulatory initiatives such as Hadopi make a lot of noise but fail at halting illegal downloads.

While the physical market remains majority until 2013, everybody in the industry has finally acknowledged the technology replacement and invest in downloads. iTunes is seen as a positive force for the music industry. But in music, everything goes fast, you remember? Too fast.

Streaming, from a slow start to exponential growth, bringing the download market to “maturity” and decline

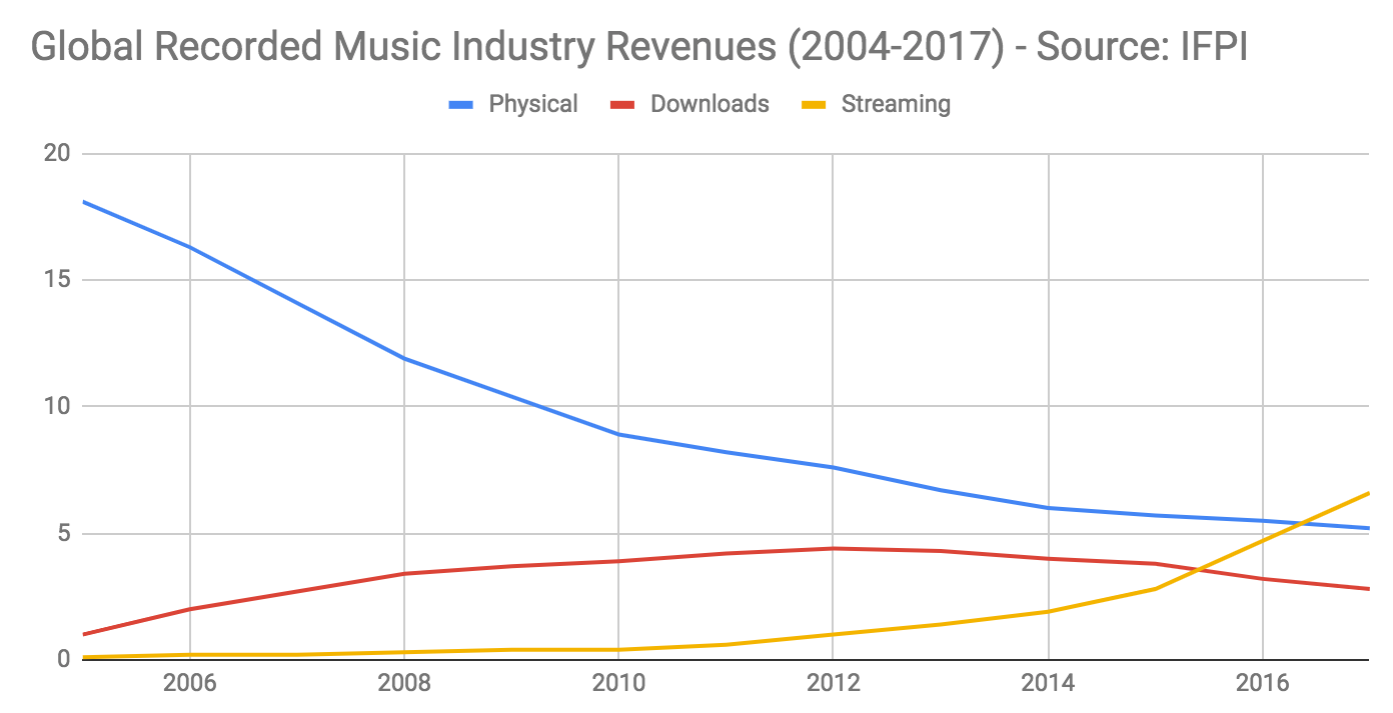

Perfect curves: exponential decline, parabola and exponential growth. Is this a math course?

Is there need for a long chat when we watch those curves?

Maybe it was because of piracy, but downloads never got to exponential growth. The frenzy was short, so was the synergy and the current maturity rhymes with… well… slow and painful death. On the contrary, if we rely only on the global revenue curves above, streaming growth looks unstoppable.

Now, another “Golden Age” for recorded music?

Without expressly mentioning it, I have been drawing a lot on Carlotta Perez’s surge of development theory in this post. From installation to deployment, she distinguishes 5 key phases: irruption, frenzy, turning point, synergy and maturity.

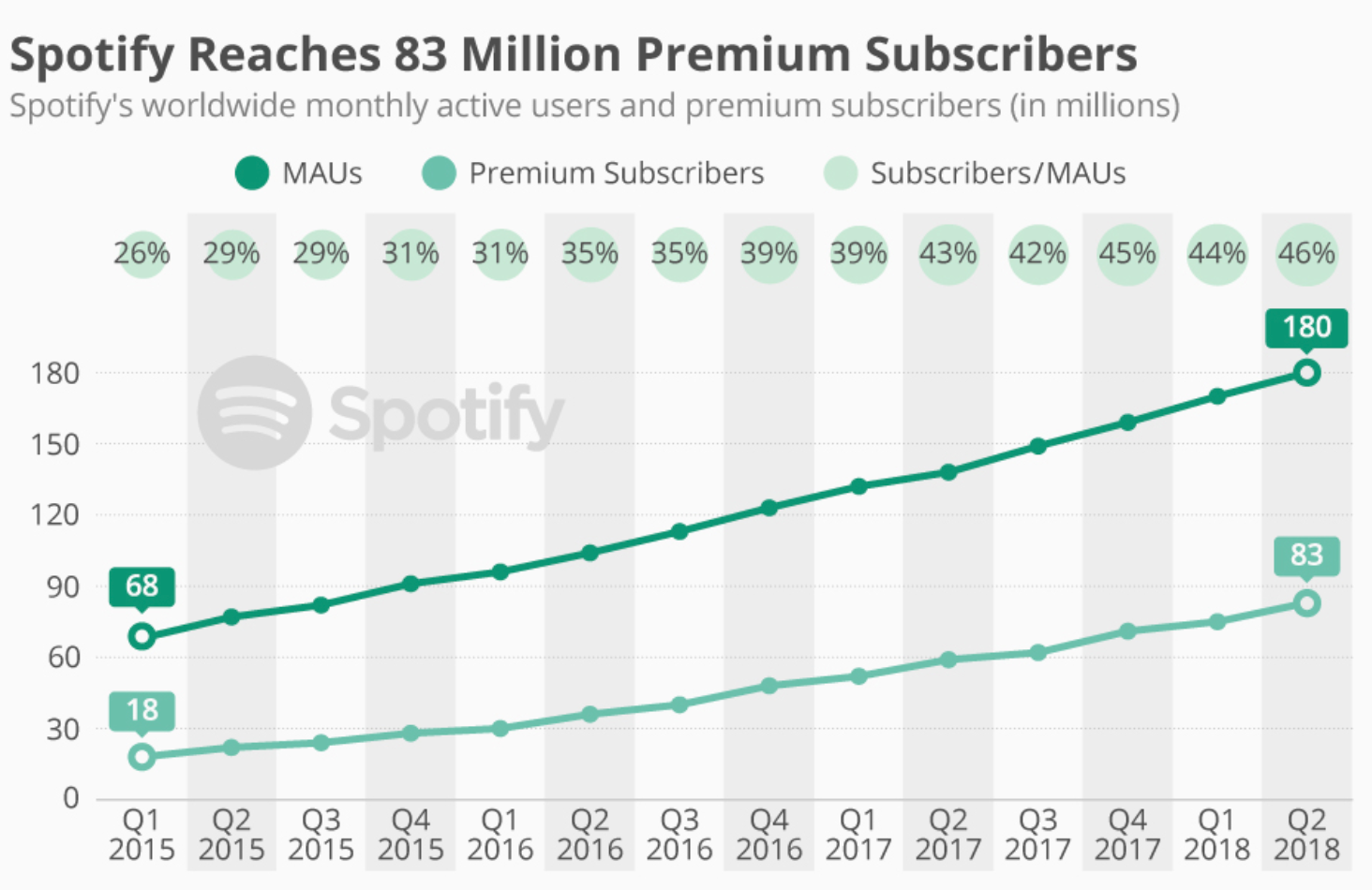

In the recent years, fierce competition between streaming services along with significant amounts of money invested in them were the characteristic of a frenzy phase. There was no certainty that revenue would grow, but signs were there, so was excitement. After the fear of people no longer willing to pay for listening to music, incredible UX experience improvements as well as huge availability of music — more than 45 million tracks are available on Deezer — allowed streaming platforms to bring more and more subscribers to their premium offers. So, there is a business model to online music finally 👏

Clean, easy-to-use, responsive. This is why people pay for Spotify. Along with its 30 million tracks catalogue.

In 2018, Spotify files for IPO on the NYSE. No longer one of the most iconic tech unicorns, the Swedish company, along with a handful other key players such as Deezer, has completely transformed the way people consume music. And February 28th — the exact date when Spotify filed its IPO — might be the turning point for streaming.

Prospective: will streaming bring about social progress for all stakeholders, including artists?

According to Carlotta Perez, the turning point paves the way for a potential ‘Golden Age’. While Spotify is still not profitable and its IPO might add to the pressure to break-even, its growth of paying users is astonishing.

With 14 million monthly active users (MAUs), Deezer is far behind its Swedish big fat green cousin

Conditions are there to drive that dynamic expansion at a healthy rhythm. It feels as if the synergy phase has already started. According to Perez model, a certain amount of prosperity is supposed to cascade to other layers of the industry. Majors — Universal, Sony and Warner — are already in a far better shape thanks to key deals signed with streaming platforms. Artists are getting paid more, even though only a few make a living out of it. €100 revenue for 250,000 paid streams vs. €100 revenue for… 100 CDs sold. This is not sustainable on the long term.

The prosperity of streaming and the music industry relies in fact on those exact promises. If this new model succeeds in fair income redistribution, in bringing fair remuneration to artists — those who make music, make the content, let’s not forget it —, then the ‘Golden Age’ could thrive and last. Helping a multitude of artists make a living out of their creations is not only a matter of music diversity, but also a major social issue. In this sense, innovations in artists services, which bring down the price to produce, distribute and promote music online, also contribute to the music industry’s health. But they are not sufficient.

Prosperity for the music business is on the way. There is hope for it to cascade to all players in the industry. In a sector where everything goes too fast — let’s remind it once again — concrete actions would need to be undertaken in order to reach that ideal. Let’s hope they succeed at the same pace as Despacito (“slowly” in Spanish”) reached 2 billion streams on Spotify.

This article was originally posted as a Medium post on December 13th, 2018 under this link.

Sources:

- Fanen Sophian, Boulevard du Stream : Du MP3 à Deezer, la musique libérée, 2017

- IFPI, Global Music Report 2018, Annual State of the Industry, Link

- Perez Carlotta, Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital: The Dynamics of Bubbles and Golden Ages, 2002, Edward Elgar

- Fildes Nic (Financial Times), Global music industry grew 8% last year jazzed by streaming subscriptions, April 24, 2018, Link

- McAlone Nathan (Business Insider), Why the music industry is poised for explosive growth, November 3rd, 2016, Link

- Forbes, Spotify Files For A $1Billion IPO, February 28, 2018, Link

- Perron Dorian (Indeflagration), Le marché de la musique en 2017 : la fin du cauchemar ? État des lieux et perspectives, May 22nd, 2017, Link